Six Dr. Seuss books will halt publication over depictions deemed ‘hurtful and wrong’

Alongside Seuss’ zany brilliance are jaw-dropping moments of racial insensitivity. Scholars argue that he evolved, however.

Six Dr. Seuss books originally published decades ago will no longer be sold because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong,” the San Diego-based company that controls the late La Jolla author’s catalog said Tuesday.

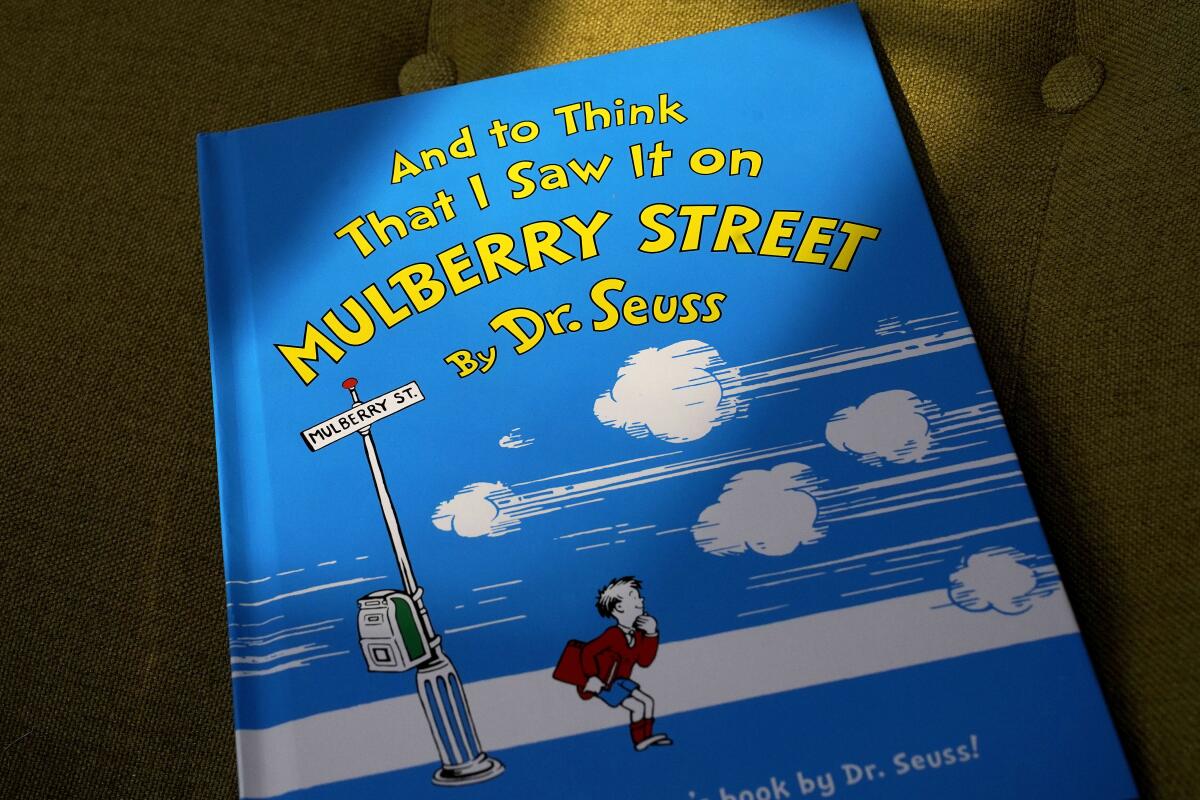

The decision, announced on what would have been Theodor Seuss Geisel’s birthday, includes his first book, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” which came out in 1937 and depicts a “Chinaman” wearing a pointed hat and carrying chopsticks and a bowl of rice.

Also being dropped are “If I Ran the Zoo,” from 1950, which has drawings of nose-ring wearing Africans and a verse about Asian workers “who all wear their eyes at a slant,” and “Scrambled Eggs Super!” which includes stereotypes about Arabs. It came out in 1953.

The others on the list: “McElligot’s Pool” (1947), “On Beyond Zebra!” (1955) and “The Cat’s Quizzer” (1976).

“Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families,” the company said in a statement.

The decision, which came after a review of the Seuss catalog by a panel of educators and other experts, thrust America’s most successful and beloved children’s author into the volatile mix of politics and culture that dominates much of the discourse these days on social media and cable television.

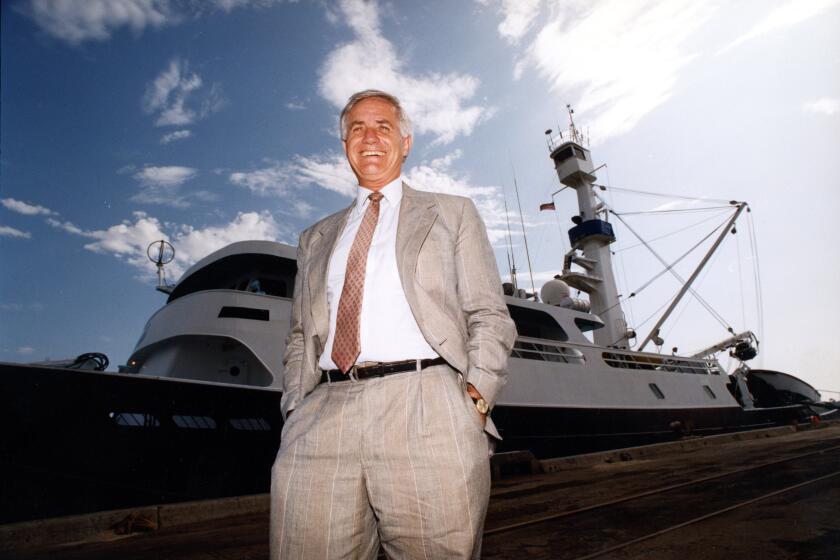

John Wilkens discusses this story on San Diego News Fix:

Some people applauded the change as part of a long-overdue racial reckoning that has also seen statues toppled, flags lowered and buildings renamed across the country. Others bemoaned what they see as a “cancel culture” that erodes the nation’s history and heritage.

Seuss, in all likelihood, would have welcomed the conversation. “It’s not how you start that counts,” he once said. “It’s what you are at the finish.”

Although he died almost 30 years ago, at age 87, the books he wrote and illustrated remain popular and influential, still used in schools, libraries and homes to help children learn to read. His four-dozen works collectively have sold more than 650 million copies worldwide, the bulk of them since his death.

When Publisher’s Weekly compiled a list in 2001 of the 100 best-selling hardcover children’s books of all time, it included 16 Seuss titles. Among them were perennial favorites “Green Eggs and Ham,” “The Cat in the Hat,” “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish,” “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” and “How the Grinch Stole Christmas.”

None of the six books pulled Tuesday were on the list, which underscores something scholars have been exploring with increasing interest in recent years: Alongside all of Seuss’ zany brilliance are some jaw-dropping moments of racial insensitivity.

In a 2017 book, “Was the Cat in the Hat Black?” Philip Nel, a Kansas State University professor, traces Seuss’ thinking to a favorite childhood story in the early 1900s, “The Hole Book,” which includes a Black mammy talking in dialect about a watermelon. Well into his 60s, Seuss could recite its opening verse from memory.

In high school, Seuss acted in blackface in one production, and at Dartmouth he drew a cartoon in which two thick-lipped Black boxers fight. In the magazine Judge, in the late 1920s, he drew cartoons of Blacks that used the N-word.

Such images were considered acceptable back then and commonly used by cartoonists, Nel writes, and as a result, “The popular culture of the early 20th Century embedded racist caricature in Geisel’s unconscious, as an ordinary part of his visual imagination.”

In the early years of World War II, Seuss drew more than 400 editorial cartoons for a New York newspaper called PM, and they showed an artist wrestling with seemingly opposite impulses. Some of the cartoons decried prejudice, and some of them perpetuated it, especially against the Japanese.

In a Union-Tribune interview after “Is the Cat in the Hat Black?” came out, Nel pointed to one cartoon as a clue to how racist imagery wound up in the Seuss books.

Seuss Enterprises says it will stop publishing 6 of his books due to racist and insensitive imagery

Titled “What This Country Needs Is a Good Mental Insecticide,” the cartoon published on June 11, 1942, shows a line of people waiting to be sprayed by an Uncle Sam figure. The man at the front of the line has just been doused, and emerging from one ear is a flying insect labeled “racial prejudice bug.” The man says, “Gracious! Was that in my head?”

Said Nel: “You appreciate the impulse there, but he conceived of racism as a bug, and that’s not how it works. It’s not aberrant, it’s ordinary. It’s not strange, it’s everyday. That’s what he doesn’t understand. Most people who aren’t targeted by racism don’t think about it. He was not unusual in that respect.”

But Seuss also evolved, and he came to regret some of the earlier work. When he realized people were offended by “Mulberry Street,” for example, he asked that “Chinaman” be changed to “Chinese man.”

He expressed embarrassed at the “snap judgments” that fueled the PM cartoons. His 1954 book, “Horton Hears a Who!” was dedicated to a Japanese friend and is seen now by scholars as an apology for the war-time drawings.

He was a doctor who made house calls, millions and millions of them, and his unique and wildly popular prescriptions influenced the way generations of children see and understand the world.

He also wrote “Yertle the Turtle,” published in 1958, which is an anti-fascist send-up of Hitler. Three years later came “The Sneetches,” full of lessons about tolerance and the evils of discrimination. He wrote an essay critical of racist humor.

“Seuss, like any other author, was a product of his time,” Michelle Martin, a specialist in children’s literature at the University of Washington, told the Union-Tribune in 2017. “Fortunately, some authors grow and figure out that maybe some of the things they wrote early on were harmful and they try to make amends. Seuss did that.”

Tuesday’s removal of the six books echoes a decision by Seuss Enterprises three years ago to take down a mural from the newly opened The Amazing World of Dr. Seuss museum in Springfield, Mass., where the author was born.

The mural, which included the Chinese character from “Mulberry Street,” had prompted three prominent children’s writers to bow out of a literary festival planned at the museum.

“While this image may have been considered amusing to some when it was published 80 years ago, it is obviously offensive” now, authors Mo Willems, Lisa Yee and Mike Curato said.

The mural was replaced with images from other books celebrating inclusion and tolerance.

“This is what Dr. Seuss would have wanted us to do,” the company said at the time.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.